IT might be the dullest smartarse pub quiz question in the world. Which professional club’s ground is closest to the Mersey? Astonish your friends by revealing it’s Stockport County. Then look deep in their eyes and realise how little they can stand you. But Edgeley Park could, and maybe should, have been denied even this admittedly pathetic distinction. Because once there was a football club, and a football ground, much closer to the river, and with ambitions to become the pre-eminent force in Merseyside football.

Pic credit: Les Ward

NOTHING makes sense in New Brighton.

Geographically within minutes of Wallasey, Hoylake and Birkenhead, the town is entirely unlike its neighbours. It’s not really in the nature of Wirral to aim for the skies, but the borough’s principal seaside resort seems perpetually in pursuit of excitement, of magic and a glamour just slightly beyond its reach.

New Brighton doesn’t have a theatre; it has a Floral Pavilion. It doesn’t have crazy golf; it has 18-hole Championship Adventure Golf with holes modelled on Augusta and St Andrew’s. It doesn’t have amusement arcades; it has vast halls full of penny falls machines, many of which don’t work but will still accept your money (this is your problem, not New Brighton’s).

Long after its peak as a genteel resort and later rebirth as a funland for the people, New Brighton is still having a go. Perhaps it’s down to geography. Sitting at the very tip of the Wirral peninsula, maybe the town’s otherness is inbuilt.

Looking out over Fort Perch Rock, it’s possible to feel pretty isolated, cut off from the rest of the world. It’s probably the furthest point in Wirral from a Homebase, at least. But really, it’s probably Sam Cooke’s other bete noire (apart from the lady who shot him) which is to blame. History seems to have dictated from day one that New Brighton would get ideas above its station.

Founded as a rich man’s folly, Liverpool merchant James Atherton christened the town in 1830 with hopes of recreating the Regency grandeur of Brighton itself. Imagine building your own resort and calling it New Brighton. What a brilliant, ambitious dickhead you’d have to be.

Like most ambitious dickheads Atherton tended to succeed at things, and New Brighton quickly grew. By the end of the 19th century it was Merseyside’s pleasure capital, hosting the city’s middle class at weekends and drawing people from across the country in pursuit of one of Victorian England’s greatest inventions – the holiday.

Across the water in Liverpool things were different. The Second City of Empire was thriving, true, but along entirely different lines. A city with a huge sectarian divide was united by a Protestant work ethic, with commerce, civic pride and religious observance the order of the day – at least outwardly.

Both of Liverpool’s major football clubs were born directly out of this environment, inextricably linked to faith and fortune, to ruthless men like John Houlding and John Orrell. Liverpool and Everton were, at one and the same time, vanity projects, community organisations, political bodies and religious totems.

Most of all, they were inevitable, necessary products of a city riven with ideological faultlines, and with a working class looking to fill the leisure hours afforded by a shorter working week.

With Everton among the game’s original aristocrats and Liverpool gaining election to the league, by the late 1890s Liverpool was firmly established as a football city.

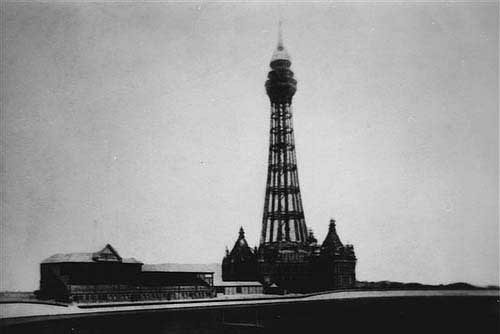

Meanwhile New Brighton was building on its own success, with ambitious plans for a tower taller than the famous one at Blackpool to become the resort’s focal point. If you’re sticking up the tallest building in Britain, no doubt an 80,000-seater athletics stadium seems pretty achievable.

And once you’ve got your 80,000 seats it probably doesn’t seem too much of a leap to have a go at creating the best team in the country to play there as a way of bringing in visitors over the winter period.

That, in essence, was the rationale behind New Brighton Tower FC. People like football, people like going on their holidays. Combine the two and what could go wrong?

In 1896 – before the tower itself was even built – New Brighton Tower FC was born. During this fluid early period, when a recently re-named Manchester City and a small team calling themselves Newton Heath were playing second division football against the likes of Darwen and Loughborough, it must have seemed like anything was possible.

And for a while, New Brighton Tower, enormous stadium and all, looked like contenders. Winning the Lancashire League in their first season, they successfully lobbied for a place in an expanded second tier of the Football League. Building, as did Liverpool, on a bedrock of Scottish imports, Tower relied on a rapid turnover of players to fuel their initial success.

Among the most notable deals was the double capture of Geordie Anderson and Geordie Dewar from Blackburn, while outside left Harry Hammond had appeared briefly for Everton before making his name at Sheffield United.

A more illustrious Blue, the England international Alf Milward, was persuaded to cross the Mersey, while fellow international (and former British baseball champion) Jack Robinson was among the first of a seemingly endless stream of goalkeepers to sign up for the Lancashire League adventure.

Despite their title win, Tower were initially denied entry to the league, but in a no-doubt entirely football-related move, the authorities expanded the league to allow the wealthy newcomers in.

And so, less than a year on from their first competitive game, New Brighton Tower were a Division Two side.

Throughout their first season attendances had been poor, with barely more than a few thousand fans turning up at the Tower Athletic Grounds. But, the owners may have been forgiven for thinking, that would all change once the people of New Brighton, and more importantly the winter visitors they imagined flocking to the town, had league football to look forward to.

Sadly, it wasn’t to be. In 1898/99 Tower started well, not losing a league game until mid November. They responded to that setback by winning seven on the bounce, including a 3-1 victory over Woolwich Arsenal.

But a dismal January and patchy run-in left them fifth, level on points with Newton Heath. It was, by any footballing measure, a successful season. But footballing measures were less important to the club’s backers than financial ones, and there the situation looked bleak. Still crowds were low. The purse strings were cut and signings more limited, with the club looking to players at either end of their careers to fill out the squad.

Then, as now, scarcer resources tended to mean poorer results, and Tower duly slumped to 10th. Key players from the previous season, including the Irish winger Charlie McEleny, were allowed to leave and were inadequately replaced. As a sad postscript, McEleny’s career would nosedive sharply, an unhappy spell at Aston Villa and short stays at non-league sides the stopping-off points on a journey that would end with his death, at 35, in a Scottish poorhouse and asylum.

With gates flatlining as Liverpool and Everton grew in popularity, it became clear the writing was gradually appearing on the wall for New Brighton Tower FC. Within three seasons the club had gone from boundless optimism to tired misdirection, with a lack of investment turning 1898/99’s progress into a huge missed opportunity rather than a positive step towards the future.

And that could so easily have been that. An essentially cynical undertaking, founded on a basis as avaricious as it was naive, was palpably running out of steam. Many, convinced by an overwhelming lack of interest in the club only accentuated by the ludicrous size of the ground, believed it might not remain in the league for 1900-01.

“Persistent rumours” of its dissolution were circulating even in 1899, according to the Derby Evening Telegraph, so after a season of relative underachievement it appeared time was running out for the fledgling club.

That New Brighton Tower not only came back for a fourth season, but signed a host of new players, was testament at least to the bloody-mindedness of the directors. Determined to have one last shot at things, sure that if only the club could gain promotion and access to derby matches, everything would somehow come right.

The club embarked on a recruitment spree, bringing in a much stronger set of players, as was noted at the time by the press:

“The directors of the New Brighton Tower Football team are showing remarkable enterprise in making preparations for next season. In addition to the captures already announced, they have just secured Herbert Dainty, the clever centre-forward of Leicester Fosse. Dainty’s engagement is regarded as the catch of the season, as he has been eagerly sought after by several First Division clubs. James Dougherty, who was considered to be the best half back in the Lancashire League last season, has also signed for the Tower club, and other important recruits are expected shortly.”

Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser – May 9, 1900

A new wave of optimism and confidence off the field translated into improved performance on it, and Tower were once again among the promotion-chasers. But the step up to the top flight was still just beyond their reach, while the people of Merseyside barely cast a glance in their direction.

Tower finished fourth, ahead of Woolwich Arsenal and Newton Heath, but seven points off champions Grimsby. Despite going the whole season unbeaten at home and recording some big wins in a low-scoring season, the season’s gates were, if anything, more disappointing than ever.

And so, after four years of uneven struggle, the club had become unviable as a business proposition and was allowed to die.

“The directors of the New Brighton Tower Football Club Saturday resolved to disband the club, and this decision has been communicated to the Football League. The collapse of New Brighton created some sensation in football circles in Liverpool. Of last season’s players J. Bell has been transferred Everton, and Goldie to Small Heath, Arridge Stockport County, and H. Dainty to Leicester Fosse. Turner and Cunliffe have returned to Portsmouth, Allison has gone to Reading, and Colvin to Luton. Such well-known players as Barrett, the old Newton Heath goalkeeper, and Holmes, half-backs Hulse, Farrell, and Hargreaves, forwards, are all disengaged.”

The Lincolnshire Echo – September 2, 1901

Today a housing estate stands on the site of the Tower Athletic Grounds. The Tower itself was torn down within 20 years, while the ballroom beneath was destroyed by fire in 1969. The big names who once threatened to put New Brighton on the footballing map are remembered, if at all, for their achievements elsewhere.

Looking back on the enterprise today it’s clear the directors launched the wrong club, at the wrong time, in the wrong place. Every decision they made was underpinned by a fundamental misunderstanding of what motivates football followers.

Then, as now, the game was not a straightforward branch of the entertainment industry. Then, as now, cash-rich neutrals with a vague interest in the game in general did exist. Then, as now, they were among the last people to put their hands in their pockets and support – in any sense – the development of a football club.

The people who made the game grow lived in major towns and cities, identified with teams bearing their names, and stuck with whatever fate threw at them from there.

At the time of writing, Hull City’s owner is issuing the FA with an ultimatum over his attempt to re-brand the club. Cardiff City have changed their kits in a bid to appeal to some notional body of fans eager to build their world around Craig Noone. The talk, up and down the country, is of “the brand.”

It’s easy for fans to deride the idea of applying business jargon to football, but there are undoubtedly brands in football. The problem is, they are remarkably resistant to change. Formed over decades, reliant on demographics as much as footballing success, they have deep roots in the game.

At the dawn of the professional game those roots were impossible to cut through for New Brighton Tower. Today they may prove thicker than ever.

First published in The Anfield Wrap Magazine.

Great article but with a few inaccuracies.. Mainly being that New Brighton isn’t a town but a suburb of Wallasey. Apparently Wallasev was the largest town in England in the 1970’s not to have a professional football club! I played at the Rackers ground in the early 70’s before it went on to become a stock car track then the current housing estate. I think that Gateshead now holds that biggest town record.,,,,

Knew about the tower but, until I read this, was unaware that there was a stadium and football club originally based in New Brighton. Fantastic piece, Steve!

Ah those exotic trips to New Brighton as a child. My sister was sent their to help her Asthma and we’d visit every now abf then. A whole new world to us. This is yet another great article, a story, some history, education and a moral. You thought about writing for Disney!?

Fascinating! Had no idea New Brighton had a tower or a football club (or was based on Brighton – although it seems so obvious now). I was going to say a football club for the Wirral might be well supported these days but then I remembered about Tranmere. In hindsight, it’s a ridiculous idea that holiday makers and visitors would go and watch football in the same way they’d go to the bowling alley etc.

Another thing I found interesting was the grandeur of New Brighton. When I was a kid in the mid 80’s we could get a train to New Brighton from Chester for 18p return, providing we went from the Bache stn which was part of Mersey Rail. We had a time where we’d go every Saturday that Liverpool weren’t at home. As with many places in the 80’s I remember it as a shit hole. I suppose, looking back, it did have quite grand buildings. It was certainly the only place within a 30 mile radius of us that had a bowling alley. How things change. I love reading any article that looks at the social, cultural, political or economical phenomenon of society but throw in a bit about football and base it on somewhere local and it’s a winner. Nice one!

Great article Steve